Will Education Be Able to Survive A.I.?

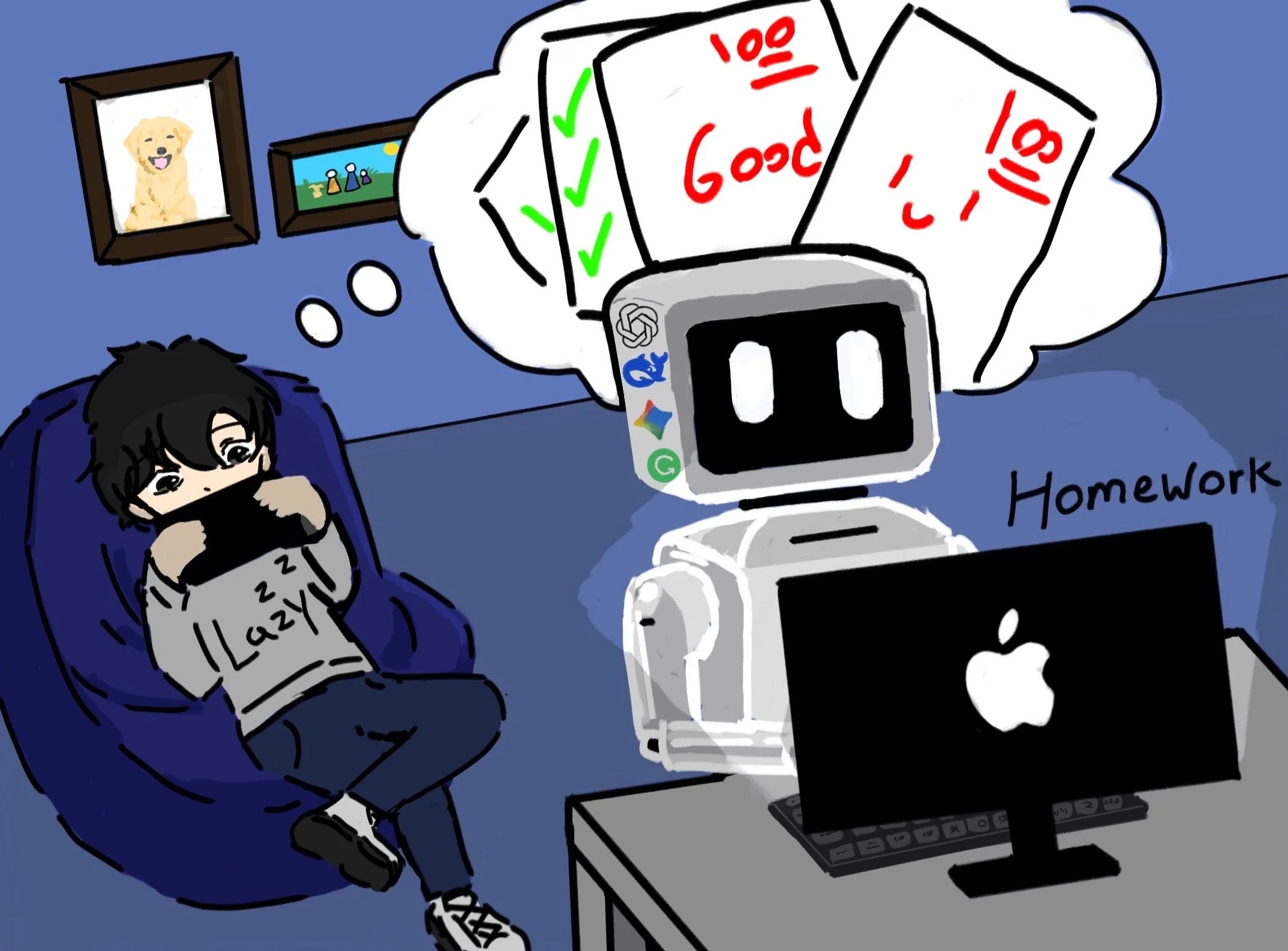

A.I. has the power to supercharge learning, but it can also be used to avoid doing thoughtful work altogether. Art: Luyi Zhang

By MUEEZ MANZOOR with ZAINAB BATOOL

Ani Kakhuashvili also contributed to this article.

Ugh! Another notetaking assignment for Weight Lifting? Are you serious? I'm just going to ChatGPT all of it.

Does that sound like you? Going through an exhausting day of school, studying for finals and grinding through extracurricular activities, only to come home to an assignment asking you to write the equivalent of a Charles Dickens novel for a class you were told was an “easy A.” It would be hard to resist the urge to tap into a little artificial assistance.

A.I. is one of the most revolutionary tools in learning, on par with calculators and the internet itself. Supporters champion its ability to give personalized tutoring and instant feedback, and to free overburdened teachers from drudgery. However, while the experience might seem bright on paper, in practice, it doesn’t match its marketing.

Artificial intelligence, specifically LLMs (large language models – think ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, DeepSeek) are weakening core academic skills, accelerating cheating, making teachers unsure if their students are even learning, and possibly ruining the education system as we know it.

Institutions that sponsor A.I. bank on the idea of goodwill, that giving students and teachers this powerful weapon will only result in it being used for good, and it’s true that if used carefully, A.I. can indeed help students clarify difficult concepts and generate practice questions. Medicine and forensic science require students to actively solve problems, and A.I. can create scenarios that help them practice these skills. “It’s the best tool to prepare for exams,” junior Entsar Abuzaid said.

But the problem is that A.I. is often used to replace learning, not enhance it.

A study conducted by Oregon State University found that when students relied on A.I. to help with their writing tasks, their comprehension dropped by 25 percent. Another study conducted by MIT found that students who used A.I. to write essays showed “less brain activity linked to creativity, memory, and executive control than those without A.I.”

Similarly, in an essay for The New York Times, college professor Anastasia Berg wrote that even small, basic uses of A.I. can be dangerous because they take away from students the important moments when they would be actively using critical thinking skills. We are in effect, renting intelligence, instead of owning it ourselves.

“A.I. is a powerful and important tool that students need to learn how to use, but it cannot replace their own work or thinking,” said Ms. Anna Nadal, a Spanish teacher. “It’s like a calculator — useful and necessary — but if you never learned how to do basic math like 12 – 5 in your head, you will struggle in many situations and become dependent on a machine for everyday tasks.”

Mr. Giovanni Gil, an Algebra II teacher, expressed similar concerns, “[A.I.] is amazing, but I worry students are using it to do the work for them, not learn from it,” he said.

We Hornets aren’t immune to this new wave. Alex Wang ‘27 typically uses A.I. for note taking. “It helps me learn concepts I might not understand, and especially helps me grasp AP Stats,” he said. “However, I often end up relying on it a bit too much instead of paying attention in class.”

Ms. Janet Gillespie, a math teacher, expressed concerns. “I worry that an overreliance on A.I. means students are missing out on the reasoning process that's foundational to understanding the how and why behind a problem,” she said. “In computer science, I worry about students letting A.I. write code for them, taking away their need to break problems down and debug their own code.”

In a recent Argus poll, students estimated that 70 percent of teens use A.I. for research and to better understand class materials, but also for doing some or all of their homework for them outright. Another Argus poll from June found that 59% of students thought “modern technology has made people dumber,” while only 26% thought it has made people smarter.

Students are truly dead set on using A.I. too; it’s no fad. GitHub (a platform built to share code and computer programs) is filled with counters to traditional A.I. detectors, as coders try to get away with secretly using the technology.

Patryk Zielinski from the University of Connecticut writes in The Wall Street Journal that students in college have begun unloading their coursework completely onto A.I., with some not even attending class at all.

In an article in The Intelligencer, Chungin “Roy” Lee, a computer science major at Columbia University (which itself is partnered, ironically, with ChatGPT’s parent company, Open AI), stepped onto the school’s campus this past fall and, by his own admission, proceeded to use artificial intelligence to cheat on nearly every assignment.

“I’d just dump the prompt into ChatGPT and hand in whatever it spat out,” he said. By his rough math, A.I. wrote 80 percent of every essay he turned in. “At the end, I’d put on the finishing touches. I’d just insert 20 percent of my humanity, my voice, into it,” Lee added.

He is one of a whole generation of learners who have stuffed themselves with the forbidden fruit that is artificial intelligence.

William, a junior at Brooklyn Tech, said, “I use A.I., but I try to limit it to simple assignments. For big ones, say Calculus, I only use it if I really am stumped. I do end up using A.I. when I am completely overwhelmed, though. Sometimes the work is just too much.”

Fundamentally, how can we counter such A.I. usage in our educational system and get students truly thinking again? If the plan is simply stronger A.I. detection software, it will only lead to an endless arms race between teachers and students with apps to detect and evade detection.

One thing we should not do is to try to pretend that the technology doesn’t exist, or that it doesn’t have any valid learning use.

LLMs certainly can help educators direct their time to the most important parts of planning and giving feedback. “A.I. helps me focus on teaching critical thinking instead of spending hours on worksheets,” explained Mr. Julio Hernandez, a Spanish teacher.

The tech can obviously be a positive for students as well. “We need to teach what appropriate A.I. use looks like: things like brainstorming, getting feedback, or checking understanding,” Ms. Gillespie said. “But we also need to set really clear expectations for when A.I. use isn't appropriate.”

One solution to the cheating issue is more in-class work and verbal assessments. Towrat Uddin ‘27 said, “A.I. should be used as a helping tool rather than something students use to cheat. The best way to prevent this is by requiring students to write down their thought process, especially for math classes and homework, and have students summarize what they did in class, since A.I. cannot replicate that.”

In addition, teachers can move back to handwritten assignments, which are making a comeback in college classrooms. A study by National Geographic found that writing with your hands engages motor skills, visual processing, and sensory feedback all at once. This multi-sensory involvement helps the brain encode and later recall information, greatly helping in overall performance in school, as well as in life. A September experiment the Argus ran with 57 Midwood students found handwriting led to a 20% improvement on memory retention over careful listening, even over the span of just two minutes.

The struggle with A.I. will likely become the defining challenge educators face this decade. As tech and time marches on, will humanity stay committed to individual learning, or give up her thirst for knowledge for the sake of comfort?